Scaling an Accounting Firm: Margin Elasticity Lessons Learned

When you're launching a startup, bookkeeping is probably the last thing on your mind. You're focused on building your product, landing customers, and maybe even raising capital. But after more than a decade of working with startups, I can tell you—ignore your financials at your own risk.

When I started GrowthLab, I wasn't thinking about accounting either and frankly, I did not offer bookkeeping or tax to my CFO customers. Then, I realized I couldn't advise customers effectively without solid and timely accounting. Therefore, how could management teams and founders understand their financial position?

Contribution Margin: What It Is and Why It Matters

In college, I learned about contribution margin, but didn’t give it much thought like most of us. In simple terms, contribution margin is the revenue left over after paying the variable costs associated with delivering your service.

For an accounting firm like mine, I always saw variable costs as mostly the direct labor – the salaries (or hours) of my accounting and analyst staff working on customer accounts – and any other expenses that increase as we serve more customers. After covering those costs, the remaining dollars "contribute" to covering fixed costs (like office rent, corporate and marketing SaaS subscriptions, my operations team and shareholder salaries, etc.) and, hopefully, provide profit.

Why is contribution margin so relevant to professional services? Because it tells you how scalable each dollar of revenue is. In a traditional firm, if I bill $1,000 per month to a customer and it costs me $700 in staff time to deliver the work, my contribution margin is $300 (or 30%). Those $300 go towards paying for overhead and profit. A healthy contribution margin means that as you grow revenue, you’ll have more left to cover new investments or generate profit. An unhealthy margin means you’re barely covering the cost of delivering service, leaving little to fund growth. I often remind my customer management teams:

pay attention to your margins. If you’re seeing only, say, 10% left after paying your direct labor, it’s a warning sign that either pricing is too low, volume isn’t hitting scale, or productivity is too low. In our industry, a gross margin (a similar concept) of around 55%-65% is considered strong (or at least until 2023!). In 2024 and 2024, many aim for something like the mid-40% range for contribution margin to sustain the business. Knowing your number gives you the fuel gauge for growth.

Elastic Margins: Why Small Changes Have Big Impact

One of the surprises I encountered but only began to appreciate in 2024 was how elastic our margins can be, in other words, how sensitive profits are to changes in revenue and costs. In an accounting business model like my company, labor is the main variable cost. This creates an interesting dynamic: if we add a bit of revenue without immediately adding staff, those extra dollars mostly fall straight to the bottom line (great for profit!). But if we lose a customer suddenly, the revenue vanishes while the staff cost doesn’t drop overnight – our margin takes a hit. In other words, our contribution margin can stretch or shrink quickly with relatively small revenue swings.

This is “margin elasticity.” It’s essentially our operating leverage. In a product business with factories or co-producers, you might have high fixed costs and low variable costs – adding sales after breakeven yields huge profit. In our services business, the cost is more proportional to work, but not perfectly. For example, if my team is at 90% capacity and we onboard a new customer, we might absorb it with existing staff initially. Suddenly our margin on that new revenue might be, say, 55% because we didn’t immediately incur new cost. But on the other hand, if we slightly over-hire or a customer leaves, we might be paying people with underutilized time – effectively that eats into margin. I’ve seen months where a small uptick in revenue made our profit jump, and other months where one lost engagement sent our profitability tumbling especially in Q1 and Q2 2024. Elastic margins mean you have to be agile and constantly forecast. I learned to watch our gross margin closely and adjust staffing proactively. As I once noted on an Ignition write-up (ignitionapp.com), it’s become “virtually impossible to find the right people at the right price, where you can justify your gross margin targets without raising your prices”.

This is a reminder that even salary changes or pricing decisions instantly ripple through our margins. For firm owners, the lesson is to build some buffer in your model and not run at 100% capacity at all times. Small changes can have outsized effects and in an industry that is moving towards upfront fixed monthly fees, forecasting short-term cash flow is about survival.

Bumping into Overhead: My 12–15 Employee Story

GrowthLab’s journey taught me about

step costs and this concept has a huge impact in the professional services business. These are those big jumps in cost structure that come when you scale past a certain point such as new hire wages. I vividly remember when we hit around 15 employees (and most were still part-time hourly and hourly billings, therefore many might experience this much sooner if you have mostly salaried employees). Up until then, I was wearing many hats: owner, salesperson, maybe even supporting customer work or admin. Our team was lean, and almost everyone was in a billable role contributing to revenue. Hitting a dozen staff was a turning point. We started feeling the strain of coordination, customer onboarding was getting chaotic, people needed HR support, and I couldn’t personally review every invoice or be everywhere at once. In other words, we needed to layer in some

non-revenue-generating roles – the very roles that don’t directly bill customers but are essential for growth.

So, most take the plunge and hire an

operations manager (to streamline our processes) and an

HR coordinator (to handle recruiting, reviews, etc). I decided to bring on team members that could fit the longer-term needs of the business as a future shareholder. At the time, I was an ambitious 40 year old and saw these moves as absolutely necessary (and still believe this to be the case, strategically) to build a solid finance-as-a-service company, but let me tell you, this

preserved my cash in the early years but cost me long-term value. This is not a personal statement but a question of velocity and magnitude of growth objectives versus a more linear approach to a stepwise growth to preserve long-term intrinsic value in exchange for short-term cash.

For many firms that take a linear hiring approach to preserve equity suddenly, find themselves covering a salary with little top-line revenue contribution. It is a classic case of adding fixed costs. As a shareholder, contribution margin drops because those costs have to be covered by the same revenue and value creation. I like to compare it to climbing a staircase: you climb steadily (adding revenue with existing resources) and then… step… you raise expenses in one jump to set up for the next climb. We had to absorb that step.

Emotionally, it isn’t easy. As a numbers guy, watching

profit margin percentage fall after the new hires was nerve-wracking. But I reminded myself (and my shareholders) that this was an

investment if you were committed to scaling. For my company, we were building infrastructure for a larger business. Many firm owners face this around the 10-15 employee mark: the realization that you need managers, HR, Customer Experience, Marketing, Sales, etc., none of which directly bill customers. If you avoid these hires, you might maintain a higher margin for now but at the cost of burning out or hitting a growth ceiling. If you embrace them, you temporarily dent your profits in order to enable future scaling. I chose the latter, and in hindsight, it was the right call – but it set the stage for a few roller-coaster years.

From $1M to $5M: A Roller Coaster Ride

Growing an accounting firm from the first million in revenue to about $5 million is a wild ride – both financially and emotionally. I refer to this phase as the $1.5M–$5M gauntlet (the first $1M is the Grind). In that range, you’re no longer a tiny practice, but you’re not yet an “established” mid-size firm with stable departments. You’re big enough to have problems (complex customers, need for policies, larger payrolls) but not big enough to have abundant resources.

For GrowthLab, this phase was marked by volatility. One quarter, we’d land a big customer, hire a couple staff to service them or lead staff, and feel on top of the world as revenues climbed. The next quarter, two startups in our customer portfolio might go bust or leave, and suddenly we’re overstaffed and scrambling to reassign team members. Revenue went up and down, and because of our cost structure, profits swung even more. I recall many sleepless nights stress-testing cash flow for the next month or 6, wondering if I’d overstretched by hiring too quickly. Emotionally, it’s draining. As a CEO, I was ultimately personally responsible for cash flow, you feel every bump personally. At times, due to the personal responsibility over the business’s solvency, I've had a neurotic relationship with growth—thrilled by every new opportunity but equally anxious about potential setbacks.

One challenge in this stage is dealing with slow-moving ROI in a high-velocity cash flow environment. What do I mean by that? In our firm, cash flow is fast, crazy fast. We bill customers monthly, and we have weekly payroll; money is constantly moving. If a customer’s payment bounces or a project scope changes, it immediately impacts our bank balance and my stress level. Yet, the ROI on big decisions (like launching a new workflow system, new business line, new technology, or hiring a senior manager) plays out over months or years. For instance, I invested in a new FP&A platform and more process automation, and even an EOS management operating system. It cost a lot upfront and took nearly a year to fully roll out. During that year, the benefit was good to minimal, but the cash flow hit was real every month in subscription fees and lost billable hours. Only later did it improve our efficiency and margins. This mismatch – spending now, hoping to reap later – can cause sleepless nights. I often felt like I was racing at high speed (managing urgent cash flow needs especially in the summer of 2024) while also trying to steer the ship toward long-term improvements that moved at a snail’s pace.

If you’re in this $1M–$5M growth phase, know that the volatility is normal. It’s like airplane turbulence; it’s unpleasant but usually a sign you’re moving somewhere. The key is to keep your nerve and make calculated and right decisions. I reminded myself constantly of a mantra:

what got us here won’t get us there. We had to accept short-term margin dips for long-term gains, and maintain faith that the investments would pay off. It helped that I had a supportive team and mentors to talk me through tough moments.

Financially, we instituted weekly cash and margin reviews and contingency plans;

emotionally, I learned to celebrate small wins and not sweat every bad month. Over time, the swings smooth out as you approach that next stage of scale.

How Hiring Hits Your Margins (a Simple Example)

Let’s break down a hypothetical scenario that reflects what many firms experience. (Numbers simplified for clarity.) Imagine you have an accounting practice doing $1,000,000 in annual revenue with a 25% profit margin. That means after paying all your staff and direct costs, you have $250,000 profit (25% of $1M). Now, you’re considering hiring an Operations Manager to help you scale. This person will cost $60,000 a year and, at least initially, won’t directly bring in new revenue.

What happens if you hire them and nothing else changes? Your costs go up by $60K, so your profit drops to $190,000. On the same $1M revenue, your margin (like in 2024 and 2025) just fell from 25% to 19%. That’s a big hit. Now, of course, the idea is not “nothing else changes.” You hired this ops manager so they can enable more growth. How much more revenue do you need to get back to your original 25% margin? Let’s crunch that: with the new hire, your annual fixed costs rose by $60K. To at least maintain your prior profit level, you need to cover that $60K. If each dollar of revenue still yields a 25% margin after variable costs, you’d actually need around $240,000 in new revenue (because 25% of $240K is $60K). In practice, that new revenue will also require some extra staff time or expenses, so the real figure could be higher. (In one real example I’ve seen, a company with a 30% margin needed about $111K additional revenue per new $65K hire just to keep margins steady. The point is: hiring comes with an expectation of future revenue.

Now, let’s say you do grow revenue by $240K over the next year (a 24% growth, not easy but feasible). You’d now have ~$1.24M revenue. With the higher cost base, your 25% margin yields ~$310K profit – you’ve more than covered the hire and even increased profit in absolute terms. But until you hit that new revenue level, you’re under water on that hire from a purely financial standpoint. This example illustrates the timing gap. There’s an upfront dip in margin and profit, followed by a catch-up later if growth occurs. As the owner, you have to plan for this dip. This is where ROI can feel slow – you might only truly “get your money’s worth” from that ops manager after 12-18 months once their impact translates into new business or improved retention.

One more scenario: what if you

don’t quickly add revenue after hiring? Perhaps growth is slower than expected, and a year later you’re only at $1.1M revenue. In that case, you might be looking at, say, $1.1M revenue against ~$850K costs (including that new hire and some other increases), leaving $250K profit – which is about a 22.7% margin, still lower than your original. You’re better off than without any growth, but you haven’t fully regained efficiency. This happens often, and it’s not a failure per se; it just means your ROI timeline extended. You might need another big customer or efficiency gain to get the margin back up.

Let’s walk through the

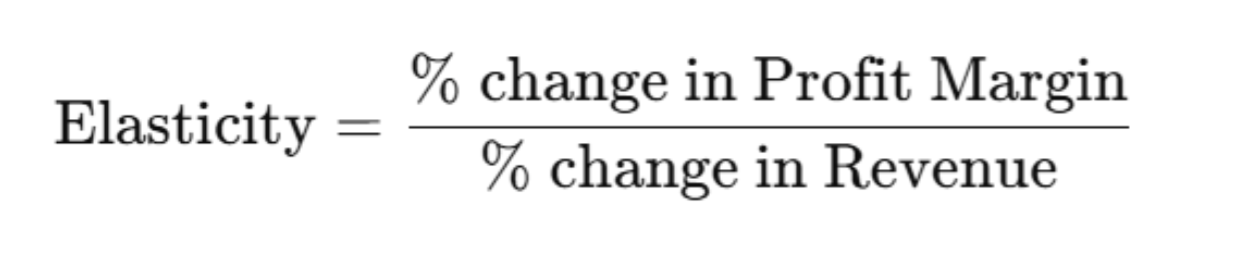

actual elasticity calculation. So we want to calculate the

elasticity of profit margin with respect to revenue, using the formula:

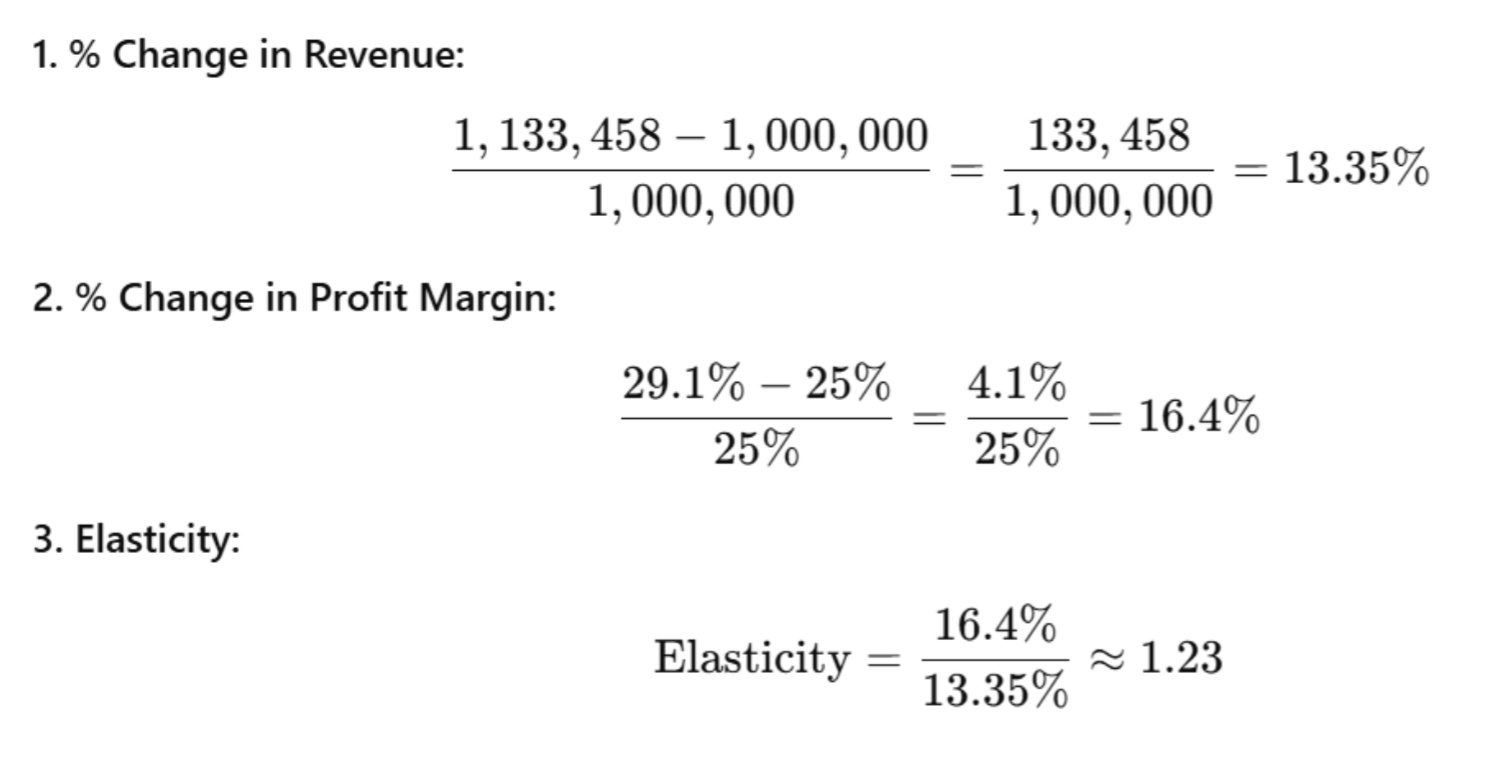

1. Example: From Base Case to Higher Revenue Case

Base Case (Before Hiring Ops Manager):

- Revenue: $1,000,000

- Profit: $250,000

- Profit Margin: 25%

Scenario: Revenue increases to $1,133,458 after hiring Ops Manager

- Revenue: $1,133,458

- Profit: $329,411

- Profit Margin: 29.1%

2. Step-by-Step Calculation

3. Interpretation

An elasticity of 1.23 means that for every 1% increase in revenue, your profit margin increases by 1.23%. This reflects positive and elastic behavior: margins are sensitive (and improve) as revenue scales due to better absorption of fixed costs.

4. Flip Side: No Revenue Growth, Just Added Costs

If you only added the $60K Ops Manager with no revenue change, your profit margin drops from 25% to 19%, or:

- % Change in Margin: (19%−25%)/25% = −24%

- % Change in Revenue: 0%

- Elasticity = undefined / infinite (this is the danger zone where fixed cost growth isn't backed by revenue)

5. Takeaway

This is why contribution margin is said to be highly elastic in service businesses. The calculus shows that small, strategic increases in revenue (especially with good contribution margins) can rapidly expand profitability, but adding fixed costs without a revenue plan causes the model to break.

I share this to emphasize the importance of forecasting before you hire. We now run scenarios like the above for every significant hire or expense:

- How much new business do we need to justify this cost?

- How long do we project it will take?

This insight gives peace of mind (or sometimes, a reality check that we need to adjust plans). It also ties back to lifestyle vs. growth choices – which leads to the final point.

Lifestyle Business or Scalable Enterprise? Choosing Your Path

Through all these experiences, one fundamental question kept arising:

What kind of business am I building? Do I want a

lifestyle business – one that stays relatively small, provides a comfortable income, and lets me (the owner) maintain a great work-life balance? Or am I aiming for a

scalable company

– a firm that could grow to a much larger size, possibly run without me in every detail, and maybe even be sold someday as a suitable company?

Neither answer is wrong. But the distinction is crucial. In a

lifestyle firm, you might decide

not to hire that extra ops manager, and instead live with a bit of chaos, to keep your margins high and stress lower. Your goal there is to sustain a level of income and flexibility, not necessarily to maximize growth. I know accounting practitioners who deliberately stop taking new customers once they reach a certain comfortable size. They prioritize personal time, stable profits, and serving a manageable customer base. If that’s your goal, you’ll approach elasticity and margins differently – you’ll try to

maximize profit now, even if it means potentially forgoing future scale.

In a scalable business, you’re willing to endure short-term pain for long-term gain. Work-life balance might take a backseat for a while as you push to grow. At the time, my shareholders and I chose the scalable route for GrowthLab. I had a vision of building something bigger than myself 12 years ago. That meant reinvesting profits into the team and infrastructure continuously. It meant some years I paid myself less so we could afford a new hire that would pay off later. It also meant thinking about leverage: I wanted to create a company that could operate as a machine, not just a collection of customer relationships tied to me in Providence, RI (I couldn’t go to a cocktail party without hearing someone stretching the truth about their business 10 years ago!). Plus, a scalable firm is easier to sell one day, because it’s built to run with solid systems, teams, and a growth engine in place, something that many firm owners don’t understand. Being part of your local business development networking breakfasts doesn’t translate into a sustainable growth engine. But it comes with risk and sacrifice and not every bet pays off, and you will work hard for possibly lower personal and shareholder earnings in the early years compared to a lifestyle practice.

My advice to other firm owners is to be intentional about this choice. If you find yourself constantly stressed by the demands of scaling (and it’s truly hammering your life and family dynamics), there’s no shame in dialing back growth, enjoying a lifestyle business, or leaving a scaling business.

On the other hand, if you have big ambitions, communicate that to your spouse and team, and make sure everyone knows the road will be bumpy and lack clarity. Neither path is easy, but the challenges are different. I briefly tried to have it both ways and realized I needed to pick a lane in 2023. For me, the thrill of building a scalable business – creating jobs, taking risks, and seeing our services reach more and more businesses – was worth the turbulence (family still thinks I am crazy at times, but my kids talk about it with their friends and my wife appreciates our efforts and employees want the rising tides). Yet I respect peers who decide that, for them, a leaner operation with higher immediate margins is the way to go.

Final Reflections

Looking back, scaling an accounting firm taught me as much about corporate finance as it did about leadership and resilience. I often say running a professional services company is a constant balancing act between people and numbers and you can’t ignore either side. Understanding concepts like contribution margin gave me a framework to make decisions: when to hire, how to price, and when to invest in overhead. But it’s the elasticity of those margins and the emotional fortitude that tested me and made GrowthLab what it is today.

If you’re on this journey, here are my key takeaways: Know your margins inside and out; expect them to wobble as you grow. Plan for step-costs like new hires or technology – they will temporarily hit profits, so have a cash cushion. Accept the roller coaster of the $1M–$5M phase; it eventually smooths out if you keep improving. Run the numbers on any big decision (like my simple hiring case study) so you go in with eyes open. And most importantly, decide what kind of business you want. That will guide your choices on reinvestment versus taking profits, on pushing growth versus holding steady.

There are other lessons focusing on ensuring the right people in the right seats, the 4 virtues of life and leadership, and innovation which today is focused on AI Automation, GTM 2.0, and the contra-AI Value Proposition: Deeper Human-in-the-Loop.

Scaling an accounting firm isn’t easy, but with clarity on these financial dynamics and your own goals, it can be a rewarding adventure. Speaking as that once anxious entrepreneur who took the leap, I can say: the view after those hard climbs is absolutely worth it. Keep learning, stay flexible, and you’ll find the right balance between margin and growth for your firm’s success.

Dan Gertrudes

As CEO and Founder of

GrowthLab Finance-as-a-Service (FaaS), Dan is the vision behind GrowthLab’s success. After spending 15 years at Fortune 500 and medium-sized companies, Dan transferred his knowledge into building GrowthLab, which now supports over 400 scaling businesses throughout their entire finance and HR value stream.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I calculate my contribution margin, and why does it matter?

Your contribution margin is revenue minus variable costs, typically calculated per service line or client.

It's critical because it helps you understand profitability before overhead. Knowing it allows you to make smart decisions on hiring, pricing, and capacity planning.

When should I make my next hire?

The right time to hire is when your team is at capacity and you have enough margin and cash flow to absorb the step-cost of a new employee.

Use forecasting models that account for ramp-up time, onboarding, and utilization rates to make this call.

What are step-costs and how should I plan for them?

Step-costs are expenses that increase in chunks—like hiring a new team member or subscribing to a new software platform.

They're not linear, so plan ahead by maintaining a cash cushion and tracking breakeven points closely during growth spurts.

Why does margin wobble during the $1M–$5M phase?

This is the stage where you start layering in infrastructure, middle management, and systems—all of which temporarily compress margins. It’s normal. The key is to monitor closely, improve efficiency, and stay disciplined about scope and pricing.

What does “right people in the right seats” really mean?

It means aligning your team members’ strengths and motivations with roles that let them thrive. This alignment is essential for scaling without burnout or churn. Regularly reevaluate roles as your business evolves.

Other Blogs Related to Startup Finance

GrowthLab, a Finance-as-a-Service (FaaS) company serving founders and management teams with full-service Financial Planning & Analysis, Monthly Accounting, Virtual CFO, HR-People Advisory, and Business Tax.